Iron (Fe) as an essential mineral for use in the body, as humans do not make our own iron (Tish, 2013) – we must consume it from food products, most well know and abundant being red meat. It also can be found in vegetables and fruit; however, the chemical make-up and actions tend to be different between these two food types, as well as how they absorbed. Red meat contains ‘heme’ iron which is utilized to make hemoglobin and ‘non-heme’ is derived from plant and fortified sources.

The iron mineral is required for essential mechanisms in the body. It is needed for ATP synthesis and used in enzyme reactions to make new DNA and also plays a role in immune system enzymatic reactions (Tis, 2013). Iron is an oxygen lover and attracts it wherever it goes: brain, muscle or blood. It is an essential chemical of myoglobin, as it helps attract oxygen in the muscle cells. Iron gives the red pigment of the blood and of course allows for oxygen carrying in the red blood cells (Iron deficiency, 2017) known as hemoglobin – which is where most of the iron in our body resides.

The ‘heme’ compound found in iron is biologically important. Non-heme and heme iron are absorbed non-competitively, however non-heme iron is not as well absorbed and heme iron. West & Oates (2008) point out that heme’s solubility increases in the presents of protein, but the actual mechanism and catabolism of iron are not well understood. Vitamin C or ascorbic acid foods have been known to increase the bio availability of iron for absorption (Hallberg, Brune & Rossander-Hulthen, 1987).

I found this diagram helpful to understand the absorption pathways (Firgure 1 West & Oats, 2008)

Iron or heme is release from proteins ingested (hemoglobin and myoglobin) via the low stomach acid and the proteolytic enzymes (Hooda, Sha & Zhang, 2014) in the small intestine and stomach.

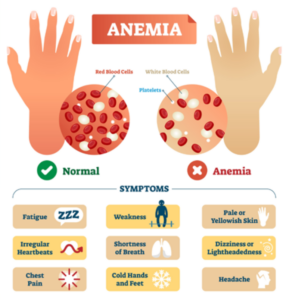

Calcium as well as soy-based foods, caffeine, tannin (found in black tea) can all compete for absorption of iron (Ford-Martin, 2018). Too little iron in our body can obviously cause a myriad of issues due to the lack of oxygen carrying, and result in corresponding symptoms: shortness of breath, fatigue, pale skin, weak nails, concentration problems, etc (For-Martin, 2018). Iron deficiency has also been associated with restless leg syndrome (Zhu et al., 2020; Restless legs syndrome, 2019). Copper deficiency can mirror iron deficiency or even cause some symptoms as copper is necessary for iron metabolism (Ha et al., 2016).

If too much iron is absorbed, then it cannot be utilized and builds up in the body and blood stream which can create imbalances in the body. It is noted that increased level of hemoproteins has been correlated with increase oxygen consumption and the progression of certain cancers (Hooda et al., 2014).

*Remember supplementing before you know the root cause could leave you with unnecessary symptoms/side effects AND wasted money and resources.

Questions!?

Kaley

MN BN CNC

References:

Ford-Martin, P. (2018). Iron. In J. L. Longe (Ed.), Gale virtual reference library: The Gale encyclopedia of nursing and allied health (4th ed.). Gale. Credo Reference: https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galegnaah/iron/0?institutionId=129

Ha, J. H., Doguer, C., Wang, X., Flores, S. R., & Collins, J. F. (2016). High-Iron Consumption Impairs Growth and Causes Copper-Deficiency Anemia in Weanling Sprague-Dawley Rats. PloS one, 11(8), e0161033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161033

Hallberg, L., Brune, M., & ROSSANDER‐HULTHÉN, L. E. N. A. (1987). Is there a physiological role of vitamin C in iron absorption?. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 498(1), 324-332. Retrieved from https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23771.x

Heidelbaugh, J. J. (2013). Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Therapeutic advances in drug safety, 4(3), 125-133. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2042098613482484

Hooda, J., Shah, A., & Zhang, L. (2014). Heme, an essential nutrient from dietary proteins, critically impacts diverse physiological and pathological processes. Nutrients, 6(3), 1080–1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6031080

Imai, R., Higuchi, T., Morimoto, M., Koyamada, R., & Okada, S. (2018). Iron deficiency anemia due to the long-term use of a proton pump inhibitor. Internal Medicine, 57(6), 899-901. Retrieved from; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5891535/

Iron deficiency. (2017). In Harvard Medical School (Ed.), Health reference series: Harvard Medical School health topics A-Z. Harvard Health Publications. Credo Reference: https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/hhphealth/iron_deficiency/0?institutionId=129

Ito, T., & Jensen, R. T. (2010). Association of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy with bone fractures and effects on absorption of calcium, vitamin B12, iron, and magnesium. Current gastroenterology reports, 12(6), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-010-0141-0

Kines, K., & Krupczak, T. (2016). Nutritional Interventions for Gastroesophageal Reflux, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Hypochlorhydria: A Case Report. Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.), 15(4), 49–53. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4991651/

Restless legs syndrome. (2019). In Harvard Medical School (Ed.), Harvard Medical School special health reports. Harvard Health Publications. Credo Reference: https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/hhpharvard/restless_legs_syndrome/0?institutionId=129

Tish, D. A. (2013). Iron. In K. Key (Ed.), The Gale encyclopedia of diets: a guide to health and nutrition (2nd ed.). Gale. Credo Reference: https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galediets/iron/0?institutionId=129

West, A. R., & Oates, P. S. (2008). Mechanisms of heme iron absorption: current questions and controversies. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 14(26), 4101. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2725368/

Zhu, X. Y., Wang, H. M., Wu, T. T., Liu, T., Chen, Y. J., Li, X., … & Wu, Y. C. (2020). SNCA-Rep1 polymorphism correlates with susceptibility and iron deficiency in restless legs syndrome. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 81, 12-17. Retrieved form https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S135380202030729X